German Cuisine and Ultra-Processed Foods

German cuisine is rich in ultra-processed foods—just think of all the sausages—but it also highlights why the current hype surrounding them is often misplaced.

I studied in Leipzig, a wonderful city, and since it was shortly after reunification, it was an exciting time. However, one memory stands out—something that I even mention in my lectures.

The food in the 'Mensa' (university canteen) was edible, but not exactly high quality. Eating, however, was a social event, and it was a good excuse for a walk across town. One day, the only decent option on the menu was something called "Jägerschnitzel" (hunter's cutlet). Typically, this is a pork cutlet served with gravy and mushrooms, usually chanterelles. I’m not a fan of mushrooms, but I figured I could just scrape them off and enjoy the rest.

When the dinner lady placed the food on my tray (using her gloved hands - not any kind of posh cutlery), I was shocked: this wasn’t a pork cutlet with gravy and mushrooms, but some kind of sausage in a red sauce. Appalled, I wondered why they would serve something so different. But none of my friends found this strange—in fact, it was exactly what they expected. That’s when I learned that in East Germany, "Jägerschnitzel" means something entirely different: it’s "Jagdwurst" (a type of sausage) served with tomato sauce.

What does this have to do with ultra-processed foods?

A lot.

Most of the data suggesting that ultra-processed foods are unhealthy come from epidemiological studies, which rely on self-reported dietary information. People describe what they eat, but for the data to be meaningful, there needs to be agreement between the participant and researcher about what different foods mean.

The most reliable way to collect dietary data is through open-ended methods, where people write down everything they eat. While keeping a food diary is often a great way to lose weight (and therefore potentially alters the diet), it provides detailed information. However, there are challenges: in one study, a volunteer recorded eating "lollies" after meals. It took some time to realise this referred to the Australian meaning (ice pops), not the British one (hard candy).

Other terms are also vague— a takeaway, a Chinese or a curry leave a lot open to interpretation. Though there are ways to address these issues, uncertainty persists.

Processing open-ended dietary data is time-consuming because someone has to decode the responses and classify them. As a result, these methods are less popular and are often replaced by structured systems with predefined categories, where participants must choose from set options.

The NOVA classification, which defines ultra-processed foods, adds even more complexity. For instance, bread is considered ultra-processed if it contains additives, but what about flour improvers (which don’t have to be declared) or bread made using high-speed mixing? And what’s the difference between homemade breaded fish (not ultra-processed) and store-bought breaded fish (ultra-processed)? Assumptions often have to be made based on population averages.

In the UK, for example, all bread is presumed to be ultra-processed, leading to misleading conclusions about children’s consumption when they bring homemade sandwiches to school. In France, on the other hand, everyone is assumed to eat artisan baguettes from local boulangerie. Such assumptions might work for broad comparisons, but they hinder our ability to link diet to specific health outcomes.

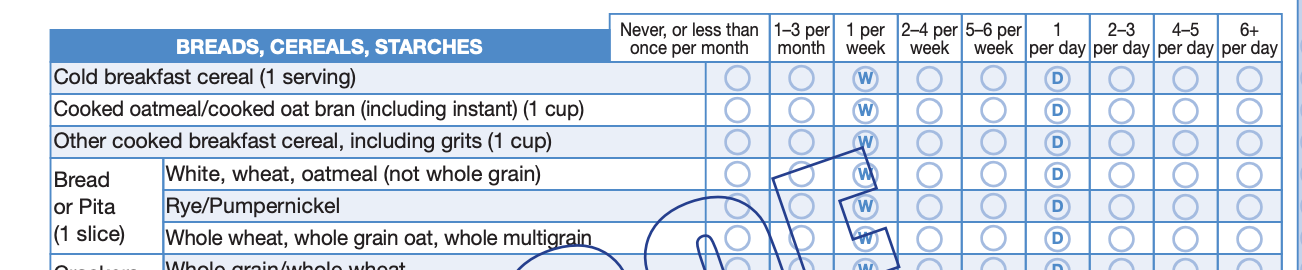

Unfortunately, most studies don’t use open-ended methods. Instead, they rely on food-frequency questionnaires (FFQs)—lists of around 100 food items that help identify dietary patterns. These are designed for specific purposes and are problematic when used for different questions. But they’re cheap, easy to process, and have become a standard tool.

Most studies investigating diet and health, including those looking at ultra-processed foods, rely on FFQs. However, these tools tend to group very different foods together. A typical FFQ might ask about wine, but it won’t differentiate between red and white. Another example: "breakfast cereal" might include anything from homemade porridge with almond milk to sugar-laden, brightly coloured cereal aimed at children—they’re treated the same in the data.

Because participants are never given the chance to clarify what they actually consumed, scientists can’t know. Yet, researchers draw conclusions from the data, claiming that people who tick "breakfast cereal" or "bread" are healthier—or less healthy—than others.

This is a major problem, and it’s why I’m skeptical about the ultra-processed food hype. If we don’t know what people are really eating, how can we draw meaningful links to health?

In a scientific setting, we’d discuss these challenges—there’s ongoing debate about how to improve dietary assessment methods. But we’ve long left the realm of science. When evidence arises suggesting that the way we measure intake might be flawed, activists often dismiss it, rather than engaging with the possibility that they might be right. In extreme cases, scientists seeking better data are accused of proposing to conduct studies on cute little hippospuppies or babies, a tactic used to shut down any meaningful conversation.

What can be done? One option is to collect more detailed data, though this has its own drawbacks. Another is to develop clear definitions of ultra-processed foods to help researchers understand what people are consuming. Or, we could use research funding to improve the UK food system and help people eat better—but that doesn’t sell books or make headlines.

Coming soon: Why we don't know much about additives.