Unpacking Food Additives: Are We Missing the Real Culprit? 🍔🔬

The NutriNet Santé Study’s Deep Dive into Additives Raises Questions About Data and Health Claims

Intro: The Additive Alarm 🚨

Headlines about food additives and their potential health risks pop up regularly, often citing the French NutriNet Santé study—for example this week about additives and diabetes risk. This observational cohort is very well designed and provides a huge amount of great data—but it is mainly the data on additives that are widely used to argue against ultra-processed foods (UPF). But does it really tell us that additives are bad? Or does it just tell us that certain dietary patterns are associated with increased disease risk.

The first question to ask here is: do they know how much additive each participant consumes? Or is it an estimate? After all, as I’ve explored before ad nauseam, shaky data can lead to shaky conclusions (see here).

Background: The Regulation Maze 🧪

In the EU and UK, food additives are tightly regulated. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) for example reevaluates them regularly. These evaluations are thorough, diving into everything from toxicology to exposure assessment—i.e. estimating how much of an additive people consume at a population level.

Here’s where it gets tricky: food composition data is often incomplete. Some companies share detailed info, but others don’t, and additive use varies depending on a product’s properties. Food isn’t standardised for science—it’s crafted for taste (even very standardised food will vary in composition for exactly that reason). Without solid data, legal limits have to be used to estimate intake. These can be strict (e.g., 150ppm for nitrite) or vague (e.g. quantum satis—“as much as needed”—for many colours); more details can be found in the EU’s food additives databases.

Still, the lack of precise data is frustrating. Just recently, the UK’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) called on industry to share more (SACN’s report). Without it, we’re left guessing:

SACN recommends that the government: […]

compels industry to make its processing data publicly available to enable monitoring and further research on associations with health outcomes - publicly available data is required on the amounts of individual additives such as emulsifiers and NSS within food products and the specific processing methods used

How is this overcome in observational studies? 📊

The NutriNet Santé team have a formidable challenge to estimate additive intake and they explain their approach in their papers. They used three sources to estimate additive levels:

2677 ad-hoc lab assays for key additive-food pairs, prioritised for common additives or those flagged for health concerns.

EFSA’s food category doses when lab data wasn’t available.

Codex General Standard for Food Additives (GSFA) doses as a last resort.

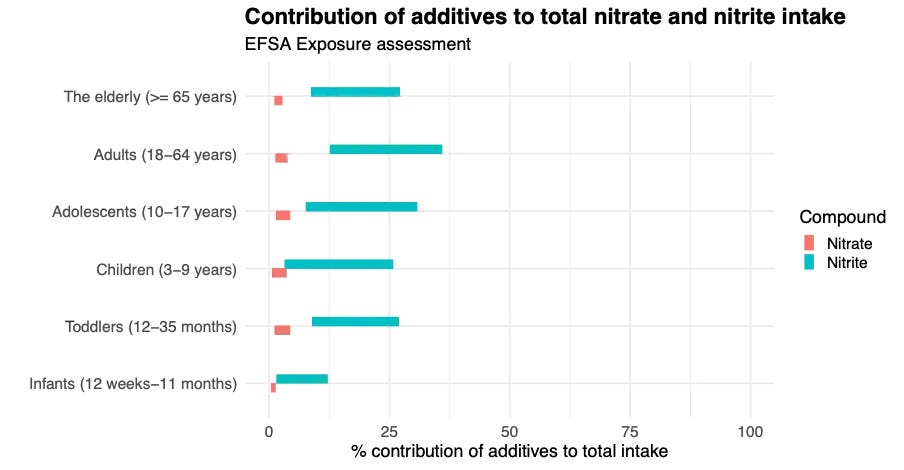

Sound familiar? The latter two mirror the exposure assessment problem: estimates, not actual measurements, are often used (and as we have shown before, this can seriously affect outcomes). Plus, many additives, like phosphates, occur naturally in foods. For nitrites and nitrates, additives are a small fraction of total intake, which muddies the health impact—your body doesn’t care if it’s “natural” or not.

What about those 2677 assays 🧪. They’re cited in most paper, and are based on the EU-funded ADDITIVES project. In a publication in BMJ, there are some more dtails: these assays covered 61 additives in 196 food items. That’s a decent start, but 196 foods is a small slice of the market. Unfortunately, we don’t know the methods used or what generic foods actually means for the analysis. Standard AOAC methods (the gold standard for food analysis) exist for many compounds, but not all. Without more information, it is difficult to interpret the results. It is difficult to understand why such great work is hidden in appendices and reports where they are difficult to find.

But even knowing these methods still raises questions, i.e. are the compounds really added or are they naturally occurring? And how does this affect health?

Table: Emulsifiers and Their Natural Roots

| E Number | Name | Occurs Naturally in Foods?

|----------|----------------------|------------------------------------

| E322 | Lecithin | Yes (e.g., soybeans, eggs) |

| E339 | Sodium Phosphates | Yes (e.g., meat, dairy) |

| E340 | Potassium Phosphates | Yes (e.g., fruits, vegetables) |

| E341 | Calcium Phosphates | Yes (e.g., bones, dairy) |

| E343 | Magnesium Phosphates | Yes (e.g., whole grains) |

| E440 | Pectin | Yes (e.g., apples, citrus) |

| E450 | Diphosphates | Yes (e.g., fish, meat) |

| E451 | Triphosphates | Yes (e.g., seafood, meat) |

| E452 | Polyphosphates | Yes (e.g., milk, meat) |What Does It All Mean? 🤔

This is the multi-million dollar 💰 question. Are additives the real culprit, or are they a red herring. Like with UPF, additives could just be a proxy for certain foods. Take the recent study flagging baking soda as tied to diabetes. Is it really the sodium bicarbonate, or is it a stand-in for, say, a cupcake obsession? 🍰

The additive debate matters. If there’s a health risk, we need to act fast. But action requires reliable data and we really need good exposure data to investigate the link between additives and health—SACN’s call for better exposure data is spot-on. Until we measure what’s actually in our food, we’re chasing shadows.

I agree with your argument in principle as someone from industry - however in practice it is often more complex. I've personally responded to data calls and tried to get smaller food producers who use the additives we supply to do so, but the reality is that not every company (especially SMEs) has resources/time to respond to such requests. They may not see why it is necessary, especially for additives that have been on the market for decades and already assessed to be safe before. It is usually the additive manufacturer who is most concerned with the safety assessment, but they don't control the exact usage by their customers (the broader usage is controlled by regulations). Some of it may also be proprietary information they may not want to disclose due to competition. This is becoming an increasingly challenging issue, especially with production/processing methods, especially in Europe due to the pressure for safety assessment approaches to be more precautionary a priori (such epidemiological papers intentionally fuel mistrust of industry even when it is not warranted - the authors position are very open about this). Hence safety assessors under such societal expectations expect complete transparency from industry - but this is also intellectual property and know how that is critical for innovation. There needs to be a balance, and it cannot also be based on the premise that industry is untrustworthy at all. That is no way to foster effective collaboration on complex scientific issues. Unfortunately there are fewer and fewer opportunities for such sharing of ideas and direct communication. The few that existed (e.g. ILSI) had been torn down due to being attacked for being ‘industry front groups. At least in the UK things are a bit better (e.g. regulatory sandboxes), but I cannot say the same for the EU.

“Unfortunately, we don’t know the methods used or what generic foods actually means for the analysis. “ …then who knows the methods and why there are not easy to find?